Differential Vector Operators

The differential vector operators and their applications.

- Physical interpretation of divergence \(\nabla \cdot\)

- Physical interpretation of curl \(\nabla \times\)

- Properties of the operators

Let \(U \subset \mathbb{R}^3\) be an open set, \(f: U \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a \(C^1\) function, and \(\mathbf{F}\) a \(C^1\) vector field on \(U\). The gradient of a function, the divergence of a vector field, and the curl of a vector field are given by the following formulas:

\[\begin{alignat}{3} \operatorname{grad} f &= {\nabla} f &&\triangleq \left[\begin{array}{l} D_1 f \\ D_2 f \\ D_3 f \end{array}\right] \\ \operatorname{div} \mathbf{F} &= {\nabla} \cdot \mathbf{F} &&\triangleq \left[\begin{array}{l} D_1 \\ D_2 \\ D_3 \end{array}\right] \cdot\left[\begin{array}{l} F_1 \\ F_2 \\ F_3 \end{array}\right]={D_1 F_1+D_2 F_2+D_3 F_3}\\ \operatorname{curl} \mathbf{F} &= {\nabla} \times \mathbf{F} &&\triangleq \left[\begin{array}{l} D_1 \\ D_2 \\ D_3 \end{array}\right] \times\left[\begin{array}{l} F_1 \\ F_2 \\ F_3 \end{array}\right]={\left[\begin{array}{l} D_2 F_3-D_3 F_2 \\ D_3 F_1-D_1 F_3 \\ D_1 F_2-D_2 F_1 \end{array}\right]}. \end{alignat}\]3Blue1Brown’s visual interpretation of divergence and curl.

Physical interpretation of divergence \(\nabla \cdot\)

Let a vector field \(\mathbf{v}(x, y, z)\) represent the velocity of a fluid at the spatial points \((x, y, z)\) and \(\rho(x, y, z)\) the fluid density. Then the direction and magnitude of the flow rate at a point \((x_0, y_0, z_0)\) will be \(\rho \mathbf{v}(x_0, y_0, z_0)\). Now consider the net rate change of the fluid at the point \((x_0, y_0, z_0)\). It can be calculated by setting up a parallelepiped of dimensions \(dx, dy, dz\) centered at \((x_0, y_0, z_0)\) and with sides parallel to the \(xy, xz\), and \(yz\) planes.

The fluid exiting the parallelepiped per unit time through the \(yz\) face located \((x_0 - dx/2, y_0, z_0)\) will be

\[- \rho v_1(x_0 - dx/2, y_0, z_0) dy dz\]where the negative sign corrects the outflow direction at \((x_0 - dx/2, y_0, z_0)\) (if \(v_1(x_0 - dx/2, y_0, z_0)\) is a negative value, pointing to the left, the outflow will be positive). For the same reason, the fluid exiting the parallelepiped per unit time through the \(yz\) face located \((x_0 + dx/2, y_0, z_0)\) will be

\[\rho v_1(x_0 + dx/2, y_0, z_0) dy dz.\]Combining the two terms, we have the outflow across the \(yz\) plane,

\[\left(\rho v_1(x_0 + dx/2, y_0, z_0) - \rho v_1(x_0 - dx/2, y_0, z_0) \right) dy dz = \left. \frac{\partial \rho v_1}{\partial x} \right\vert_{(x_0, y_0, z_0)} dx dy dz.\]The partial derivative is used because \(v_1\) also relies on \(y, z\). Finally, by adding the contributions from the other four faces of the parallelepiped, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \text{outflow} & =\left[\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\rho v_1\right)+\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(\rho v_2\right)+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(\rho v_3\right)\right] d x d y d z \\ & =\nabla \cdot(\rho \mathbf{v}) d x d y d z . \end{aligned}\]Intuitively, the divergence measures the net outflow at a spatial point. A positive divergence implies a source whereas a negative one indicates a sink. The physical system in which fluid are neither created or destroyed will lead to the continuity equation, of the form

\[\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \mathbf{v}) = 0.\]Physical interpretation of curl \(\nabla \times\)

Given a vector field \(\mathbf{F}\), consider the line integral \(\oint \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{s}\) for a small closed path. Again, we consider the closed path to be a small rectangular in the \(xy\)-plane (\(z=0\)) with two sides parallel to the \(x\) and \(y\) direction and centered at a point \((x_0, y_0)\). Now the line integral along the segment 1 can be computed as

\[\text { segment 1} = \int_{x_0-\Delta x / 2}^{x_0+\Delta x / 2} F_1\left(t, y_0 - \Delta y / 2\right) d t \approx F_1\left(x_0, y_0 - \Delta y / 2\right) \Delta x\]where the approximation holds by the mean value theorem. Similarly, we can compute the line integrals along the other three sides

\[\begin{aligned} \text { segment 2} = & \int_{y_0-\Delta y / 2}^{y_0+\Delta y / 2} F_2\left(x_0+\Delta x / 2, t\right) d t \approx F_2\left(x_0+\Delta x / 2, y_0\right) \Delta y, \\ \text { segment 3 }= & \int_{x_0+\Delta x / 2}^{x_0-\Delta x / 2} F_1\left(t, y_0+\Delta y / 2\right) d t \approx-F_1\left(x_0, y_0+\Delta y / 2\right) \Delta x, \\ \text { segment 4 }= & \int_{y_0+\Delta y / 2}^{y_0-\Delta y / 2} F_2\left(x_0-\Delta x / 2, t\right) d t \approx-F_2\left(x_0-\Delta x / 2, y_0\right) \Delta y. \end{aligned}\]By adding the integrals of segment 1 and 3, and those of segment 2 and 4, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \text {segment 1+3} &= \left(F_1\left(x_0, y_0 - \Delta y / 2\right) - F_1\left(x_0, y_0+\Delta y / 2\right) \right) \Delta x \approx - \frac{\partial F_1}{\partial y} \Delta y \Delta x \\ \text {segment 2+4} &= \left(F_2\left(x_0 + \Delta x / 2, y_0\right) - F_2\left(x_0-\Delta x / 2, y_0\right) \right) \Delta y \approx \frac{\partial F_2}{\partial x} \Delta x \Delta y. \end{aligned}\]Hence, we have

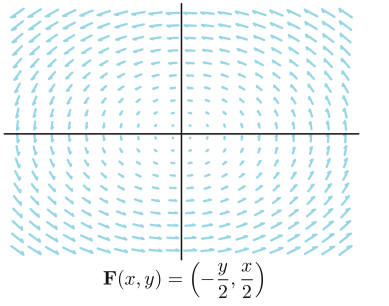

\[\tag{circle-integral}\label{eq:circle-integral} \oint \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{s} \approx\left(\frac{\partial F_2}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial F_1}{\partial y}\right) \Delta x \Delta y \approx[\nabla \times \mathbf{F}]_3 \Delta x \Delta y.\]The first approximation actually mirrors the Green’s Thorem which states the line integral around a closed path equal to the corresponding integral over the closed area. By the Green’s Thorem, the line integral in Eq. \eqref{eq:circle-integral} is nonzero only if the stream line forms a closed loop. To form a closed loop, a stream line must curl, this is where the name comes from. The value of the line integral per unit area is called the circulation. The circulation is roughly the force with which the current spins the paddle wheel counterclockwise as shown in the below figure.

Why might you expect the expression \({\partial F_2}/{\partial x}-{\partial F_1}/{\partial y}\) to measure the circulation? This expression is positive when \({\partial F_2}/{\partial x}\) is positive and \({\partial F_1}/{\partial y}\) is negative. \({\partial F_2}/{\partial x} > 0\) means that the \(y\)-component of \(\mathbf{F}\) increases as \(x\) increases, so the current has more upward push against the right side of the paddle wheel than the left, causing counterclockwise spin. \({\partial F_1}/{\partial y} < 0\) means the \(x\)-component of \(\mathbf{F}\) decreases as \(y\) increases, so the current has more rightward push against the bottom side of the paddle wheel than the top, again causing counterclockwise spin.